Abstract

Quantum computing research accelerated following Shor’s 1994 factorization algorithm invention, which promised polynomial time integer factorization capable of breaking RSA, and subsequently elliptic curve cryptography; however, three decades of development reveal fundamental engineering obstacles, qubit noise, decoherence timescales measured in nanoseconds, and threshold theorem redundancy requirements of to physical qubits per logical qubit, that render practical cryptographic attacks implausible with current or foreseeable future technology.

Historical Context and Algorithmic Motivation

Shor’s algorithm1 provided initial impetus for quantum computing investment by demonstrating that integer factorization, exponential time on classical computers, becomes polynomial time on hypothetical quantum systems, directly threatening public key cryptography. Grover’s search algorithm2 followed, offering quadratic speedup for unstructured search problems; these theoretical results generated substantial research funding despite absence of physical implementations capable of meaningful computation.

Qubit Implementation Diversity and Noise Characteristics

Physical qubit implementations span diverse quantum systems; a Google Scholar search for “quantum computing with” reveals attempts using optical systems, ion traps, superconducting circuits, topological states, nuclear magnetic resonance, quantum dots and almost anything that exists.3 Most experimental systems employ optical configurations or superconducting Josephson junctions as in D-Wave systems;4 however, all implementations exhibit inherent noise from electron spin fluctuations, measurement induced decoherence, and crosstalk between adjacent qubits operating on nanosecond timescales.

Reading state from ten qubits requires nanosecond precision timing while tolerating measurement induced errors; practical systems require qubits where x scales with problem complexity, creating formidable engineering challenges for coherent state maintenance and parallel readout across large qubit arrays.

Error Correction and Redundancy Requirements

Threshold theorem5 addresses noise through redundancy, permitting fault tolerant quantum computation if physical error rates remain below specific thresholds; however, implementation requires to physical qubits per logical qubit depending on error rates and correction codes employed. Factoring 1024 bit RSA modulus requires approximately quantum logic gates for ;6 applying threshold theorem redundancy yields to physical qubits needed.

Physical implementation constraints eliminate these configurations; implemented qubits employ superconducting Josephson junctions rather than theoretical point particle spins, requiring macroscopic physical infrastructure. While tunnel barriers measure approximately 100 nanometers, necessary shunting capacitor pads and control resonators expand single qubit unit cell footprint to millimeter scale dimensions; Google Sycamore processors demonstrate qubit center to center spacing approaching 1 millimeter. Assuming hypothetically optimized micrometer packing density, a qubit processor demands monolithic chip surface area of 100 square kilometers maintained between 10 and 20 millikelvin.7 Thermal load from millions of kilometers of control wiring necessary for qubit addressing exceeds any conceivable refrigeration capacity, boiling refrigerant instantly8.

D-Wave’s 2020 announcement of 5'640 noisy qubits represents progress toward single error corrected logical qubit under optimistic threshold assumptions, not toward systems capable of useful computation.

Compiled Algorithm Limitations

Compiled Shor algorithm variants reduce qubit requirements through classical preprocessing that exploits prior knowledge of factorization; Martin et al. demonstrated a three qubit compiled implementation factoring 15 with 48% success probability given advance knowledge that factors are 3 and 5.9 This result, requiring both classical knowledge of the answer and accepting majority failure rate, illustrates the gap between theoretical algorithmic promise and practical implementation capability.

Current State Assessment

As of 2021, quantum computing implementations cannot factor 15 using pure Shor’s algorithm without classical preprocessing assistance; noise mitigation remains unsolved despite threshold theorem providing theoretical framework; no physical system demonstrates reliable execution of elementary arithmetic operations like or on quantum hardware without classical verification. The field exhibits characteristics of speculative research sustained by theoretical promise rather than empirical progress toward stated applications.

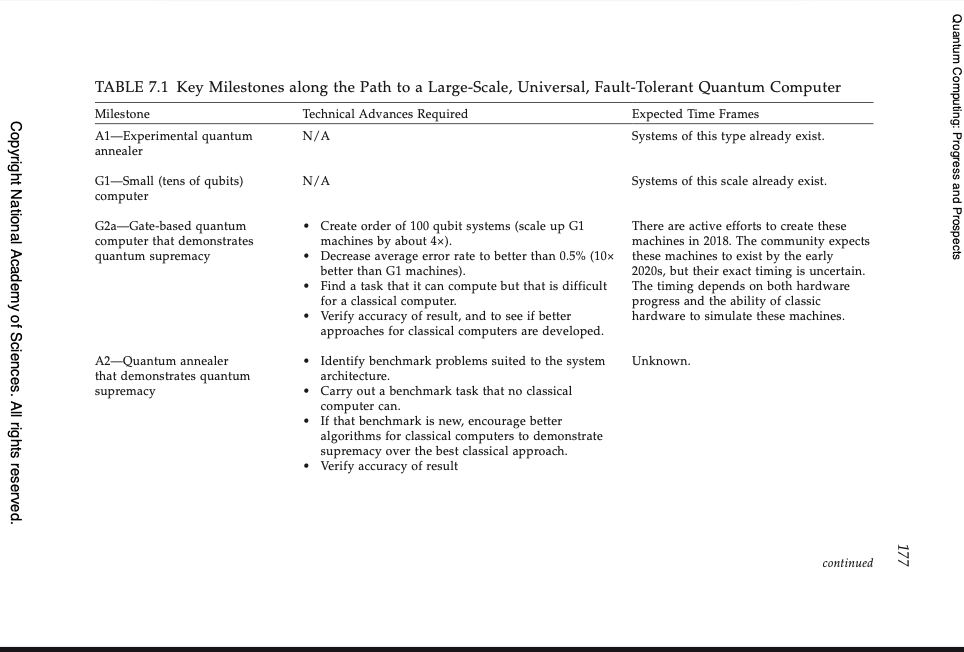

The 2019 National Academies assessment10 evaluated progress against milestones established during initial 2000s funding initiatives; after two decades and billions in research expenditure, the report documents minimal advancement on original objectives, fault tolerant quantum computation, scalable qubit architectures, and cryptographically relevant factorization, prompting strategic pivot to Noisy Intermediate Scale Quantum (NISQ) systems and redefinition of success criteria toward identifying any task where noisy quantum hardware demonstrates advantage over classical computation, however marginal or impractical.

This strategic retreat from original cryptographic and optimization promises toward NISQ applications exemplifies field dynamics where continued funding requires redefining objectives downward when initial goals prove unattainable.

Marketing narratives around quantum computing achievements merit scrutiny; D-Wave’s February 2021 announcement claiming performance advantage in quantum simulation of exotic magnetism11 generated substantial media coverage asserting million fold speedups, yet careful examination reveals the underlying Nature publication12 employed only four physical qubits while citing 1'440 in the abstract as classical Ising model spins, not quantum bits.

Supplementary materials compare performance against D-Wave’s own classical emulator designed to simulate precisely four qubits,13 rendering the comparison circular rather than demonstrating genuine quantum advantage over optimized classical algorithms. This pattern, where press releases emphasize qubit counts or speedup factors while obscuring that systems operate on trivially small problem instances or employ favorable classical baselines, recurs throughout quantum computing literature.

Critical analyses by Locklin14 and Dyakonov15 document additional fundamental obstacles including decoherence, scalability limits, and measurement problems that compound the redundancy requirements discussed here.

Postscript

This analysis was written in early 2021; subsequent four years have seen incremental increases in qubit counts and modest improvements in coherence times but no fundamental breakthroughs addressing the scaling obstacles described here. The core thesis, that physical constraints render cryptographically relevant quantum computation implausible, remains valid as of late 2025.

In early 2024, Google announced a five million dollar prize through XPRIZE for identifying practical quantum computing applications that demonstrate algorithmic advantage over classical systems;16 the necessity of offering substantial financial incentive to discover use cases for technology that has consumed billions in research funding over three decades substantiates the critique that quantum computing remains a solution searching for problems rather than a practical computational paradigm addressing genuine needs.

February 2025 witnessed Microsoft’s unveiling of “Majorana 1”, heralded as the world’s first topological quantum processor intended to scale to one million qubits; however, the accompanying Nature publication carried an unprecedented editorial disclaimer stating the results “do not represent evidence for the presence of Majorana zero modes” in the reported devices17. Independent analysis characterized the signal data as indistinguishable from random noise, confirming the device demonstrated neither non Abelian braiding nor quantum information storage, but merely a lithographic architecture for unproven physics; the gap between the corporate announcement of a “breakthrough” and the academic reality of unverified quasiparticles further illustrates the industry’s reliance on projected rather than demonstrated capability18.

May 2025 brought mathematical confirmation of fundamental noise mitigation limitations. Zang et al. proved “No-Go Theorems for Universal Entanglement Purification”19, demonstrating that no protocol implementable through local operations can universally improve fidelity across entangled states subject to realistic, nonidentical noise patterns.

This result strikes at the heart of scalability: realworld qubits exhibit independent, time varying error profiles due to differing memory wait times and environmental fluctuations. The theorem establishes that “blind” purification, improving states without precise prior knowledge of their specific errors, is impossible. This creates an engineering paradox: correcting errors requires characterizing the noise in real time, yet the necessary benchmarking consumes the very resources and time constraints required for computation. The finding validates that noise management is not merely a hurdle of capacity, but a fundamental algorithmic impasse.

The triviality of current quantum factorization achievements received definitive demonstration when subsequent work20 replicated all quantum factorization records, numbers 15, 21, and 35, using a VIC-20 8-bit home computer from 1981, a standard abacus requiring only two or three columns, and a dog trained to bark numerical values; the satirical nature of this replication highlights that three decades after Shor’s algorithm, quantum computing’s celebrated factorization records remain at computational complexity levels achievable by technology predating personal computing or, indeed, by manual calculation devices from antiquity. The paper’s methodology, providing cycle accurate 6502 assembly implementations and abacus operational procedures alongside canine based protocols, underscores the disconnect between quantum computing’s theoretical promise of breaking modern cryptography and its practical demonstrations factoring numbers trivially decomposable through inspection or elementary arithmetic; when achievements warrant replication guides suggesting “any animal shelter” as adequate hardware sourcing, the field’s claimed progress merits skepticism.

Peter Shor, “Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring”, Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 1994. ↩︎

Lov Grover, “A fast quantum mechanical algorithm for database search”, Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, 1996. ↩︎

Search performed on Google Scholar for publications containing “quantum computing with [substrate]” reveals hundreds of attempted physical implementations across fundamentally different quantum systems. ↩︎

D-Wave Systems progressed from 128 qubit systems in 2011 to 5'640 qubit Advantage systems announced for 2020; all operate with noisy intermediate scale quantum (NISQ) qubits without error correction. ↩︎

The quantum threshold theorem establishes that quantum computation becomes arbitrarily reliable given sufficiently low physical error rates and polynomial overhead in qubits and gates for error correction. ↩︎

Estimate derives from Shor’s algorithm complexity analysis requiring quantum gates for factoring bit integers, with constant factor approximately 72 from circuit compilation studies. ↩︎

Frank Arute et al., Quantum supremacy using a programmable superconducting processor, DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1666-5 ↩︎

Hypothetical 100 fold packing density improvement combined with optimistic physical qubit threshold requirement necessitates 1 square centimeter footprint per logical qubit; at this scale thermal load creates immediate engineering impasse. Realistic assumption relaxation requiring redundancy for noise suppression or density target failure expands single logical qubit surface area to 10 square centimeters, rendering system cooling physically impossible. ↩︎

E. Martín-López et al., “Experimental realization of Shor’s quantum factoring algorithm using qubit recycling”, Nature Photonics 6, 773–776 (2012). arXiv:1202.5707 ↩︎

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Quantum Computing: Progress and Prospects, 2019. Report documents systematic failure to achieve fault tolerant quantum computation milestones despite two decades of substantial research investment. ↩︎

D-Wave Systems, “D-Wave Demonstrates Performance Advantage in Quantum Simulation of Exotic Magnetism”, press release, February 2021. ↩︎

A. D. King et al., “Observation of topological phenomena in a programmable lattice of 1'800 qubits”, Nature Communications 12, 1113 (2021). Despite title referencing 1'800 qubits, actual quantum computation involved four qubit subproblems; larger numbers refer to classical Ising spins in simulation target. ↩︎

D-Wave Systems path integral Monte Carlo simulator, available at github.com/dwavesystems/dwave-pimc, implements classical simulation of small qubit systems; comparison against this specialized tool rather than general purpose optimized classical algorithms inflates apparent quantum advantage. ↩︎

Scott Locklin, “Quantum computing as a field is obvious bullshit”, January 2019. ↩︎

Mikhail Dyakonov, Will We Ever Have a Quantum Computer? Springer, 2020. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-42019-2 ↩︎

XPRIZE Quantum Applications, available at www.xprize.org/prizes/qc-apps. Prize specifically seeks algorithms demonstrating quantum advantage for practical applications, implicitly acknowledging absence of demonstrated utility despite decades of development. ↩︎

Nature Editorial Board note appended to Microsoft Quantum’s February 2025 publication; the journal explicitly clarified that while the device architecture was novel, the experimental data failed to substantiate the existence of the topological state of matter claimed in simultaneous press releases. ↩︎

S. Aaronson, FAQ on Microsoft’s topological qubit thing, Shtetl-Optimized, February 20, 2025. Critics noted that the “Topological Gap Protocol” used to validate the device produces false positives from trivial Andreev bound states, rendering the “topological” claim mathematically unsound without demonstrated braiding statistics. ↩︎

Allen Zang et al., “No-Go Theorems for Universal Entanglement Purification”, Physical Review Letters 134, 190803 (2025). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.134.190803. The authors prove that for non-identical input states (a necessary condition of real hardware), no LOCC protocol can guarantee fidelity improvement without a priori knowledge of the error model. ↩︎

Peter Gutmann, “Replication of Quantum Factorisation Records with an 8-bit Home Computer, an Abacus, and a Dog”, IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive 2025/1237 (2025). Available at eprint.iacr.org/2025/1237. Demonstrates that all quantum factorization records as of 2025 can be matched using 1981 consumer hardware, manual calculation tools, or canine based computation; satirical presentation emphasizes triviality of achievements celebrated as quantum computing milestones. ↩︎